Do YOU Trove?

On Saturday 8 August 1857, an 18-year-old woman, recently emigrated from England, won a court battle in Melbourne’s Old Court. The plaintiff’s name was Emma Steer, and she had arrived in Australia from Elstree, Hertfordshire in 1852 with her mother, father, two sisters and a brother. Newspaper articles available through Trove show that within four years of the Steers’ arrival in Victoria a set of circumstances arose that changed their lives. The Steers ran a small unspecified business in Essendon, Victoria in rented premises. Their landlord, known as Fitches, also owned the pub next door. Sometime during 1854 Fitches’ son took a fancy to young Emma and set out to woo her, intimating marriage. Her parents assented to this overture, and the two young people began spending time together. One spring evening around 8.00 pm, while they were walking home through a paddock, Fitches junior “had his way” with Emma, all the while promising that marriage would follow. She became pregnant; he ran off with someone else. It could have ended in misery, perhaps it did, but it appears that Emma was resilient. With the emotional support of her parents, but without any other means to speak of, Emma filed for breach of promise and seduction. Steer vs Fitches was heard in two separate trials at the Old Court during August 1857; Emma was represented by the Attorney-General of Victoria, Mr Ireland. She won both cases and was awarded 150 pounds for the first charge, and 60 pounds for the second. Emma Steer was my great great grandmother.

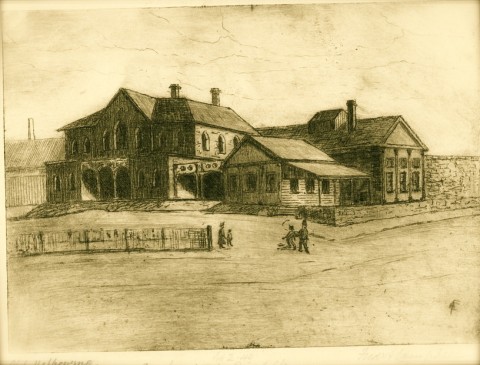

Melbourne’s Old Court at time of Steer vs Fitches

All I knew of Emma Steer was the bare bones – the date of her arrival in Australia, the fact of her marriage to my great great grandfather, the children she subsequently bore, and the date of her death. My research in Trove had focused mainly on the men; after all, when we look at records from the 19th and early 20th centuries, it is their stories that dominate. They were the ones who bought land, set up businesses, sat on parish councils, got drunk and created havoc, invented things and took out patents. Having found little about my great grandmother Jessie (see photo), I assumed there would be even less about Emma. But thanks to the nationwide newspaper digitisation project instigated by the National Library of Australia (NLA), Emma Steer – born in 1838, boarded the ship The Persian in 1852, married Alfred Whitlock in 1861, had nine children, died in 1880, and was buried somewhere in Bendigo – has suddenly come to life. I don’t know what she looked like or what kind of regional English accent she must still have had; I don’t know what happened to the illegitimate baby she bore, or how she met Alfred and explained her complicated history to him; but I know she had guts (sisu). And, as I discussed at a recent forum at the NLA, this emotional dimension of discovery, this question of affect and context in the construction of knowledge, may turn out to be the real treasure at the heart of Trove.

out of the dark ages

Digital historian, Tim Sherratt considers Trove to have lifted digital humanities research “out of the dark ages.” Trove, along with the other cultural archives Sherratt tinkers with, is more than a huge cache of data, it is a “repository of feeling.” A letter, a newspaper article, a photo, a patent, the name of a ship – produce an emotional connection to the past, which “opens us up to new ways of thinking about the material and the constructing of stories around that material.” (Sherratt, RN 2012). While Trove has many windows and doors, the most intense traffic is via the newspaper digitisation pathway. This is also the area from which innovative practices have emerged, like the crowd sourcing of OCR (optical character recognition) text correction, active online discussions, social media, the use of the Trove’s Applied Programming Interface (API) to develop interrogative tools like Sherratt’s QueryPic and Headline Roulette and, importantly, the phenomenon of autonomous communities that are finding ways to connect with each other and share learning in a digital space. Lubna Sultana, a speaker at the forum, has studied the motivational factors behind the army of text correctors who, between them, have corrected over 76 million lines of text over the last couple of years. Some meet in their local library, while others do it alone from home, but all are motivated by a public service ethic to make this extraordinary archive more accurate and searchable. Physicist John Rayner, another speaker, has surveyed Trove’s digitised cache of The Australian Women’s Weekly from 1933 to 1982, mapping trends in the way the magazine has approached scientific developments and news. When genealogist Amy Houston was having trouble keeping up her self imposed blogging schedule, she decided that one thing she could do was share weekly finds in Trove with others. Trove Tuesday was born and now has a dedicated band of regular bloggers. And we know something has caught on when it turns from a noun into a verb. Amy Houston told me that one of her Trove Tuesday bloggers coined the phrase Do YOU Trove? “She didn’t write a blog one week and she was like ‘I love Trove, do you Trove too?'” recounts Houston. “She’s turned it into a verb, and to justify her decision she says if you can Google, then you can Trove.” (Houston, 2012)

Jessie Whitlock, cutting cake for troops on Henty Railway Station, 1916

a memory prosthetic

With the aid of portable devices, Trove is now becoming a memory prosthetic. Monica Redden and her siblings recently visited their 89-year-old mother in Jamestown, South Australia. A bit frail and hard of hearing, Nora Redden finds talking with more than one person at a time slow going these days. Using an iPad, Monica accessed Trove to gather ‘memories’ of her mother’s past as a champion tennis player in Booborowie, a small town 200 kilometres north of Adelaide. Local newspapers from the 1930s and 40s contained numerous tournament details and glowing portraits of Nora’s tennis playing talents. “Mum is typically kept out of conversations these days,” said Monica, “but she was fully engaged in the discussion, it brought back all of these beautiful tennis memories about who she played with and how she felt when she played a particular game. Then my brother Nick said let’s look up Uncle Jim, because the Murphy boys were great footballers, and Mum said, no, this is my turn Nicholas, and it’s about me and tennis.” Annual cabarets and balls, which were big events in small country towns in the early 20th century, were also extensively reported during this time. As Monica read out the names of attendees, including those who brought lamingtons and cream buns, more memories were triggered. Combining an iPad with Trove makes sharing memories and stories a collective experience. “It’s a lot of fun too,” says Monica, “and a great way to connect with older people.”

“Australians are empowered by Trove, but they are also powering Trove with new insights, enthusiasm, and interest in sharing Australian stories.”

The media we consume can often, even unconsciously, proscribe our reactions because the information and ideas presented have passed through the perceptual filter of someone with the ‘authority’ to speak, thereby implicitly telling us what to think. As Sherratt notes, the strong connections that arise from our contact with the material now available through Trove are “largely unmediated”; there is something about these raw encounters with the past that feels fresh. Emma Steer’s story has touched me in ways that I don’t fully understand, and has become a talking point for my extended family. And 89-year-old Nora Redden (Murphy) has been able to conjure up a past that is creating new meanings in the present. If this isn’t a treasure, what is?

First published in 2013. Republished to support #fundTrove.

The National Library of Australia has provided me with access to internal documents and the opportunity to interview a range of people. I want to thank Debbie Campbell and the Trove team in particular for their generosity, time and knowledge.

References

Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 – 1918), Tuesday 11 August 1857, page 2, 3 (Steer vs Fitches)

Houston, A. (2012) Interview with author

National Library of Australia, Inspired by Trove, 28 February 2013, podcast

Redden, M. (2013) Interview with author

Sherratt, T. (2012) Exploring Digital History, Inside History, September-October 2012, p.55

Sherratt, T. (2012) Reinventing Archival Records, Future Tense, ABC Radio National, December 16, 2012

State Library of NSW, photo of Jessie Whitlock, part of At Work and Play – images of rural life in NSW 1880-1940 (available through Trove)

State Library of Victoria, photo of Old Court: http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/72021 (available through Trove)